This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

FILM, ART AND THE SMARTPHONE

FILM, ART AND THE SMARTPHONE

28 Nov 2019

In our digital age, the way art is made and seen has changed, with the camera phone now an ever-ready paintbrush, particularly for the moving image. How did film get to this point? We ask Arts Society Lecturer John Francis.

Shutterstock

Shutterstock

WHEN DID THE CONCEPT OF FILM AS ART START?

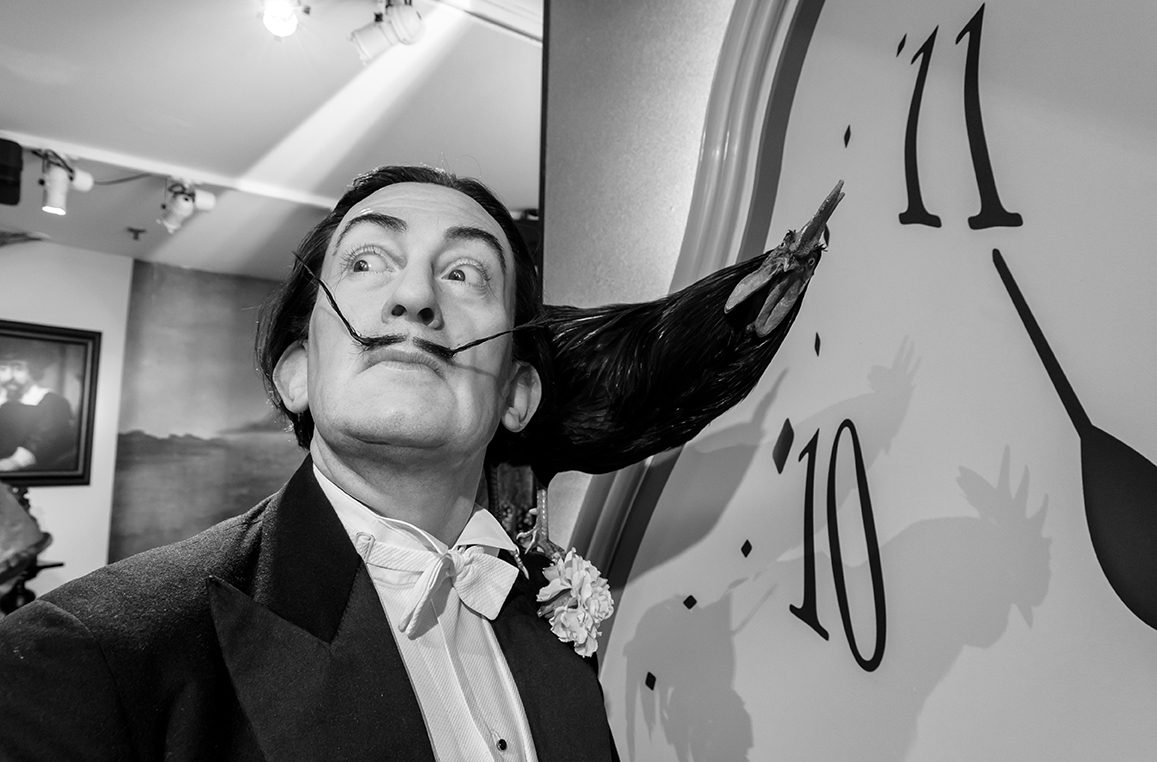

In the 1870s, when Eadweard Muybridge added time and movement to the image, enabling artists to discover a new form of canvas. French and Spanish Surrealists were also fascinated by the medium. Black-and-white film-making did not cost much and gave opportunities to tap into the subconscious. Salvador Dalí had dreams of a hand crawling with ants, while film-maker Luis Buñuel ‘saw’ a cloud in the sky that sliced the moon in half. Film was the obvious medium to represent such subconscious. They collaborated on the 1929 Un Chien Andalou, a work with no plot, but loaded with Freudian free association. It inspired generations of artists and film-makers. Ironically, the film attacked the bourgeois with barbed comments on moral conventions, yet was embraced by a conservative society as a new art form.

DID FILM ENABLE NEW FORMS OF EXPRESSION?

Moving images offered the artist endless visual possibilities. The 1930s Italian Futurists were excited by the potential that celluloid possessed to capture the movement and energy of the Modernist city with its fast motor cars, whistling machines and dynamic rotating views. In 1927 Berlin, Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin, Symphony of a City was perhaps the most influential ‘documentary’ film, portraying the reality of modern life. The film plays with abstract images, tempo and rhythms of the city, while carefully recording daily life. Visual kinetic imagery is given a musical expression.

Allene Ray Stunt Woman, New York, USA, 1925, Underwood Archives/UIG/Bridgeman Images

Allene Ray Stunt Woman, New York, USA, 1925, Underwood Archives/UIG/Bridgeman Images

WHICH KEY ARTISTS HAVE DEVELOPED FILM AS ART?

Andy Warhol stands out: he was fascinated by technology. He took the easel painters’ portrait to a new form with his 1960s 16mm representations of (mostly) celebrities. His series of short, black-and-white film portraits, Screen Tests, used just a Bolex camera and a 100-foot roll of black-and-white film, with no editing or direction. The three-minute films were slowed to four minutes when projected in an art gallery. This slow motion of ‘living portraits’ gave a dreamy realism to the finished work.

WHAT DID THE DADAISTS DO WITH FILM?

Discarded bus tickets, magazine adverts, restaurant bills and more were the sources of the collages of German Dadaists, such as Hannah Hoch and Kurt Schwitters. The Dadaist Movement was a revolt against traditional academic art and the absurdity of war. ‘Found’ imagery was later taken up by New Zealand artist Len Lye. In his work in the innovatory GPO Film Unit, Lye borrowed film footage from a variety of sources to include in his ‘camera-less’ films. In these musical ‘adverts’ his fingerprints can be seen as he dabbed and splashed colour onto raw film stock. In his 1937 animation Trade Tattoo, commissioned in support of a ‘post early’ campaign, Lye combines abstraction with ‘found’ floating images of ships, dock workers, welders and trains.

Still from Bye Bye Kipling, 1986. Courtesy of Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York and the Estate of Nam June Paik

Still from Bye Bye Kipling, 1986. Courtesy of Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York and the Estate of Nam June Paik

AS A ‘NEW’ MEDIA, HAS FILM BROUGHT FRESH IDEAS?

The recycling of media images to create a second or third meaning has been embraced, for example in the video work of Scottish artist Douglas Gordon. Gordon, a Turner Prize winner (1996), pays homage to Alfred Hitchcock in his 24 Hour Psycho, in which he stretches Hitchcock’s masterpiece into a slow 24-hour experience, forcing the audience to reconsider the moving image in a new way. As an art installation it sculpts time, while playing with our memories and narrative expectations. Gordon monumentalises the moving image, while the Korean Nam June Paik (who died in 2006) was the artist who first discovered the potential of new, cheap video technology. Called the ‘father of video art’, he considered not just the flickering imagery of broadcast global TV, but also saw the object ‘box’ of the television set as a way to build works of digital sculpture, stretching the possibilities of moving digital image and sculpture.

Hockney Self portrait, 14 March 2012, © David Hockney

Hockney Self portrait, 14 March 2012, © David Hockney

IS DRAWING STILL IMPORTANT IN THE ART/FILM PROCESS?

Drawing remains the starting point for painting and animation, with some artists now reaching for digital tools when doing so. Think of David Hockney, who uses apps found on the iPhone and iPad. Drawing is the building block to great art and a good example is the work of South African artist William Kentridge, who has been working with charcoal drawing and film for the last 30 years. His expressionist drawings are a complex convergence of image, music, puppetry, drama and installation art.

WHO ARE THE BIGGEST ‘NAMES’ IN FILM ART AT THE MOMENT?

Bill Viola and Gillian Wearing. They employ video to document everyday life and its emotions. Viola examines the core human experiences of birth, death and love, while Wearing seeks to blur the line between reality, ritual and fiction. Viola has been called ‘the Rembrandt of the video age’. Wearing focuses on the disconnect between our inner lives and our public personas. For both, the video camera functions as a ‘microscope of being’, marking life’s milestones and minutiae. Their work is immersive to the viewer and humanist in outlook.

Charlotte Prodger – Photo Emile Holba

Charlotte Prodger – Photo Emile Holba

WHICH ARTIST IS A TOP EXAMPLE OF SOMEONE MAKING ART WITH A SMARTPHONE?

Charlotte Prodger, who won last year’s Turner Prize with her critically acclaimed exhibition Bridgit/Stoneymollan Trail. It’s over 80 years since German critic and philosopher Walter Benjamin suggested that painting possessed a certain ‘aura’, which photography did not. Prodger’s work definitely has an ‘aura’, which viewers and commentators find compelling. She explores issues surrounding queer identity, landscape, language, technology and time. Her work is a prime example of how the ubiquitous phone and camera have integrated into the personal creativity processes and physical workings of today’s artist.

OUR EXPERT’S STORY

John Francis, Arts Society Accredited Lecturer

• John trained as a painter and was once the artist-in-residence for the state of Texas

• He has produced and directed several short films and animations

• He has also taught film, art and pedagogy at universities as far-flung as Exeter, Malaysia and California

• John lectures on everything from Hitchcock’s mastery of suspense to Revolt into Style: The Punk Aesthetic – Fashion, Art and Music

SEE

Nam June Paik Tate Modern’s major exhibition of the work of the visionary Korean artist, whose name is synonymous with the electric image.

17 October–9 February 2020

tate.org.uk

MAKE A DATE

David Hockney: Drawing from Life includes iPad drawings by the artist.

27 February–28 June 2020

npg.org.uk

About the Author

John Francis

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition