Very successful raffles held at each monthly lecture enabled The Arts Society Taunton to distribute 100 bags filled w

An Optical Illusion

An Optical Illusion

14 Jul 2020

An optical illusion?

by Jeni Fraser

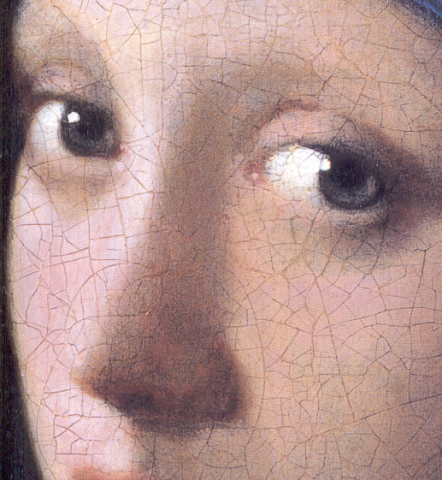

Vermeer, The Girl with a Pearl Earring, c. 1665, Mauritshuis, Amsterdam

At the same moment that Johannes Vermeer was painting his masterpiece Girl with a Pearl Earring, the English king, Charles II, was busy amusing himself with optical illusions. By positioning the heads of prisoners in his blind spot, the king entertained himself by rehearsing the decapitation of the condemned before the executioner did so on the chopping block. Strange as it may seem, the two phenomena – Vermeer’s masterpiece and the monarch’s macabre pastime – have a great deal more in common that you might suppose.

We now know that our blind spots – those ophthalmological quirks at the back of the eye where the cluster of nerves greatest a gap in vision – do not appear as blank spaces in our sight because our brains fill in the missing information from the patterns they perceive around us. Whether consciously or not, Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring is a clever case-study in cutting edge-optics, whose power relies on precisely this capacity of the human mind to fabricate what is not there. Look closely at the girls’ face, which seems to have turned towards us, and so much of what we believe defines her features is merely implied rather than explicitly articulated.

Are you convinced she has a nose? Examine closely and you will soon discover that what you thought was a delicately delineated bridge has, in fact, dissolved without a trace into the supple skin around it. Only a soft shadow cast against her left cheek – just enough to signal to our brain that, in context, a nose should be there – conjures the feature.

Two deft smears of paint and the swollen teardrop around which the painting’s mysterious story spins is magicked into existence by the primary visual cortex of our brain’s occipital lobe from a few tiny clues. No matter how hard you peer, there is no hook that links the shiny bauble to the girl’s earlobe. The earring levitates, propelled into suspension a much by our minds as by any substantive crafting by the artist.

Simply put, Vermeer did not paint a pearl – he told our brains to go and fetch one. Rather than mimic the way the physical world actually looks; Vermeer’s sleight of hand teases the imagination into creating in the mind’s eye a more vibrant image than a brush can forge.

A speck of bright moisture adorns the corner of her mouth, which is open as though she is about to speak. Her words, though, remain a mystery. Unlike some of his Dutch contemporaries, who crammed their compositions full of material objects and narrative detail, Vermeer got a kick out of teasing the viewer and withholding meaning – and, just like solving a puzzle, the enjoyment is found in constructing a narrative.

About the Author

Jeni Fraser

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Lytham Hall, an exquisite Grade I listed Georgian house designed by John Carr of York, stands as a testament to 18th-