This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Paul Gauguin's Great Selfies

Paul Gauguin's Great Selfies

15 Oct 2019

What did Paul Gauguin’s self-portraits say about him? To coincide with a major new exhibiton at the National Gallery, Arts Society Lecturer Juliet Heslewood reveals the back stories to some of his rawest works.

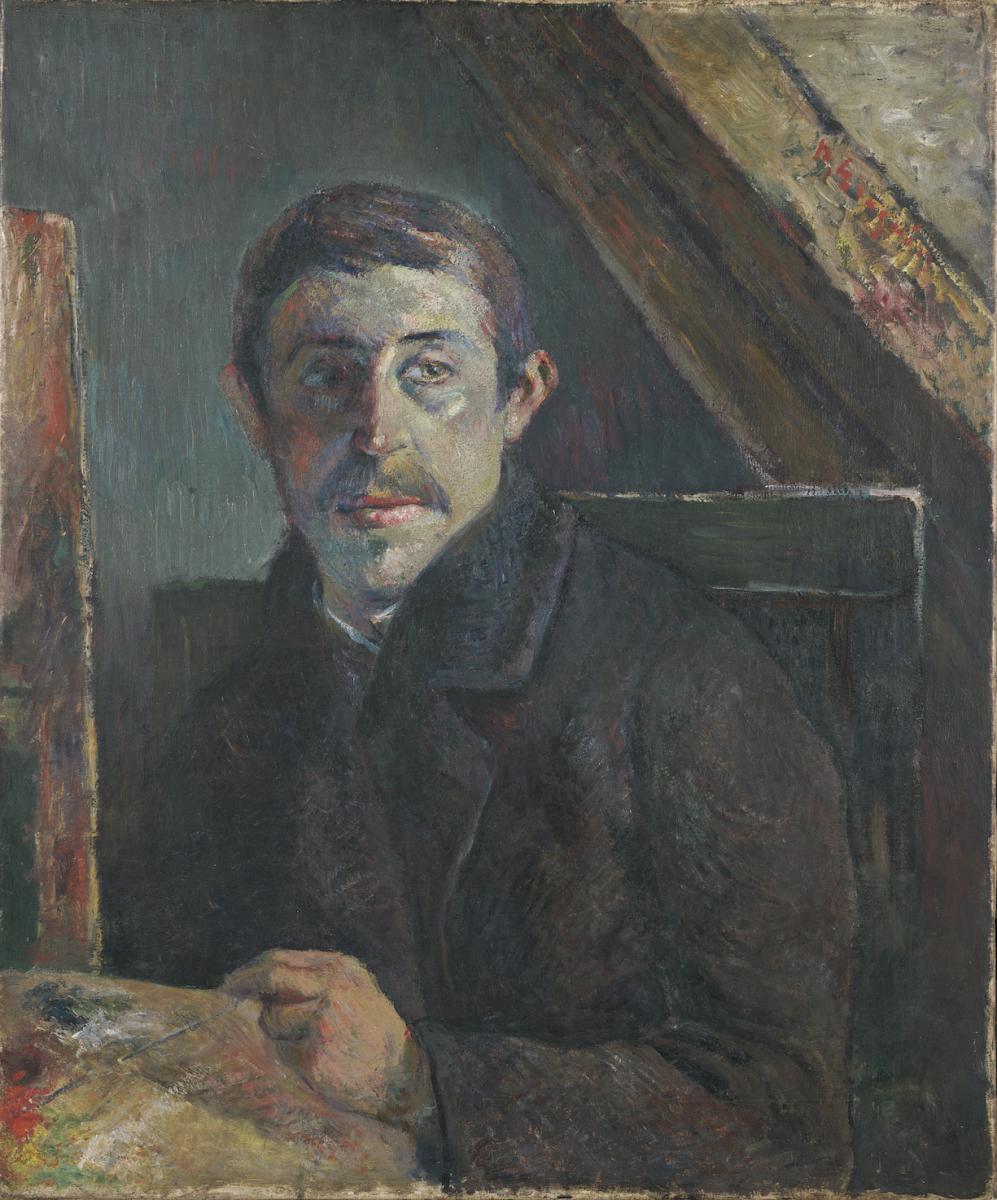

Self-Portrait, 1885. © Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas

Self-Portrait, 1885. © Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas

Artists frequently use their own faces as a convenient model, or to study expression and facial anatomy. Rembrandt’s self-portraits present a lifetime’s observation of the ageing process. Frida Kahlo’s paintings become her autobiography. Gauguin’s self-portraits reveal his questioning sense of identity – and his artistic mission – at different times during his fascinating life. An early work, his Self-Portrait of 1885 shows him holding a palette and brushes – the attributes of artists – but with a departure from the usual self-portrayal. When a painter has to look in a mirror, the eyes in the portrait appear to focus ahead, as if at ‘us’. But here Gauguin’s eyes look away to a single source of light, the only relief in a narrow, dark environment. The painting was made in Copenhagen, where his wife, Mette, and his children had moved to be near her family. Though no longer with a respectable income, Gauguin gained some work there, including as a tarpaulin salesman, but, unpopular with his in-laws, he retreated to an attic. Here he painted and wrote about the contemporary art scene.

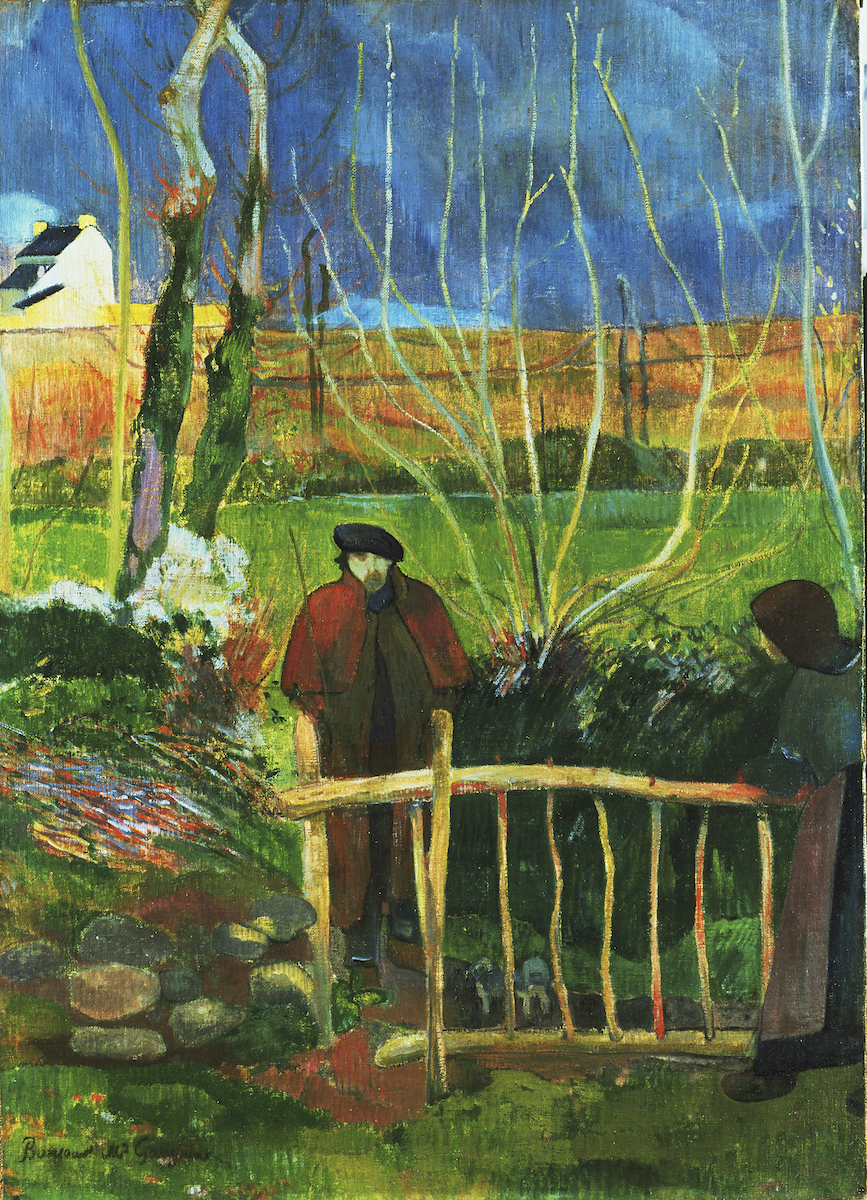

Bonjour M. Gauguin (I), 1889. The Armand Hammer Collection. © The Hammer Museum, Los Angeles

Bonjour M. Gauguin (I), 1889. The Armand Hammer Collection. © The Hammer Museum, Los Angeles

Gauguin hoped that once he had gained success in the art world, he and his family would be reunited. In 1886 he discovered Brittany, a cheaper place for him to advance his work. In his 1889 Bonjour, M. Gauguin (I) he appears as a shabby wanderer, observed with some reserve by a Breton peasant. Standing on the other side of the gate he separates himself from her, as if a stranger. In Brittany, where he adopted not only clogs, but also the traditional embroidered waistcoat he included in several other works, he found his way ahead to be clearer: ‘I find here the savage and the primitive,’ he wrote, adding: ‘When my clogs resound on this granite earth, I hear the dull, muffled tone, flat and powerful, that I try to achieve in painting.’

Christ in the Garden of Olives, 1889. © Norton Museum of Art

Christ in the Garden of Olives, 1889. © Norton Museum of Art

By 1890 Gauguin’s work had met with little critical approval, though he hoped to make as big an impact as Seurat with his innovatory pointillism. One startling, bleak image of himself is as Christ in the Garden of Olives. In this he shows himself with bright orange hair, which contrasts with shaded blues in a dream-like garden, from where the disciples flee. He explained that it represented the crushing of an ideal, desolation and a powerful synthesis of pain.

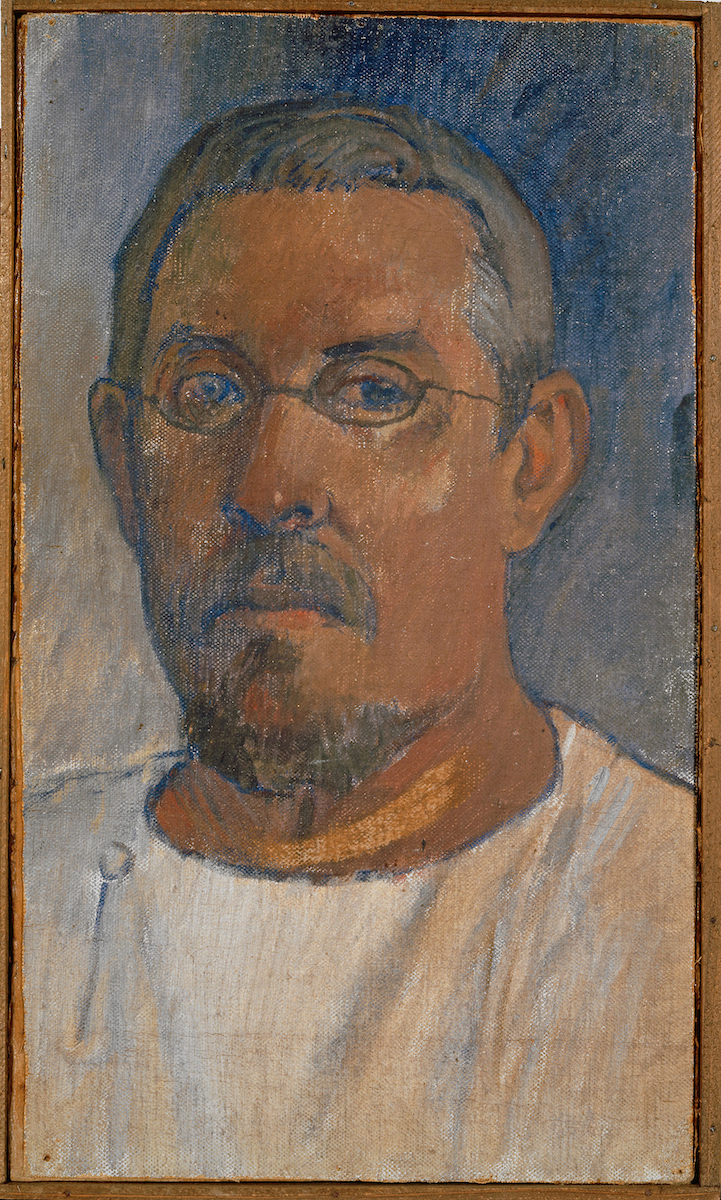

Self-Portrait, 1903. © Kunstmuseum, Basel

Self-Portrait, 1903. © Kunstmuseum, Basel

Gauguin’s years in Tahiti were fraught with difficulties. It was not the Eden he had hoped, where people’s lives reflected their beliefs. He found a society now dominated by French officials antipathetic towards him. Gauguin’s exotic Eve did not exist. Women were forbidden to go bare-breasted and forced to wear buttoned-up European-style clothes. Yet in Tahiti his imagination, informed by dreams of old idols and old ways, encouraged original, brilliantly coloured work that still, unfortunately, enjoyed little commercial success. During a temporary spell in Paris he painted his studio bright yellow and hung on the walls new work from Tahiti. He included the one he was most proud of, Manao Tupapau (or Spirit of the Dead Watching), seen in mirror image behind him in another powerful self-portrait of 1893–94.

Juliet Heslewood is an Arts Society Lecturer and art historian. She is the author of many books, the latest of which is Van Gogh: A Life in Places.

SEE

The Credit Suisse Exhibition: Gauguin Portraits

The National Gallery, until 26 January

SIGN UP

Read Juliet Heslewood's extended feature on Paul Gauguin's self-portraiture in the autumn issue of The Arts Society Magazine.

About the Author

Juliet Heslewood

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition